A beautifully crafted, technically perfect work of literary art. So cleverly planned, every word carefully chosen. One could make the criticism that Charlotte Brontë made of Jane Austen’s novels – “I should hardly like to live with her ladies and gentlemen in their elegant but confined houses” – but that is a category error.

I feel I cheated in that I knew beforehand, from publicity about the book and the later film, that Stevens, the first-person narrator, is unreliable. While reading the book I was highlighting those words and sentences that I guessed would be contradicted by later actions or revelations. It would have been interesting to have opened the book completely ignorant of it.

Is the buttoned-up, repressed character of Stevens a believable one? Why not? People from previous generations were flesh and blood creatures like ourselves, but they were also conditioned – as we are – by their upbringing and the conventions and constraints of their times. There’s perhaps no limit to the ways people will adapt to circumscribed lives in order to survive and even prosper.

Stevens focuses on the notions of professionalism, duty, service, dignity and loyalty and shies away from attachment. He is paralysed emotionally (the reader only learns that he has been crying through other people’s words; he “only” reads romantic novels for their elegant phrases) and morally. When Lord Darlington – in his Mosley phase – demands that any Jewish staff be sacked, Stevens only regrets the loss of good workers, whereas Miss Kenton is (impotently) angered, and even Lord Darlington eventually regrets his order and tries to make amends. Stevens is – quite chillingly – detached from such decisions (in contrast to Mr Harry Smith post-war, who regards it as every person’s duty to be informed and have an opinion on current affairs, and is therefore constantly disappointed).

Throughout the years I served [Lord Darlington], it was he and he alone who weighed up evidence and judged it best to proceed in the way he did, while I simply confined myself, quite properly, to affairs within my own professional realm. And as far as I am concerned, I carried out my duties to the best of my abilities, indeed to a standard which many may consider ‘first rate’. It is hardly my fault if his lordship’s life and work have turned out today to look, at best, a sad waste – and it is quite illogical that I should feel any regret or shame on my own account.

In such a subtle novel, there are no black and white judgements to be made. Perhaps in Nazi Germany, Stevens would have been a monster, but as an English butler such potential is never tested (his “crimes confin’d”). Lord Darlington is not simply a Nazi apologist: his motives, grounded in Germany’s post-WWI plight, are noble, but he is misguided, manipulated, and – as the American ambassador insists – an amateur. Contrasted with Stevens’s depressing professionalism, however, is being an amateur so dreadful? Even post-WWII, when you expect a collective sigh of relief at the creation of the welfare state and the loosening of deference, there are ambiguities about the new world. Dr Carlisle seems to have lost his hope in socialism to change people; he acknowledges that they just want to be left alone.

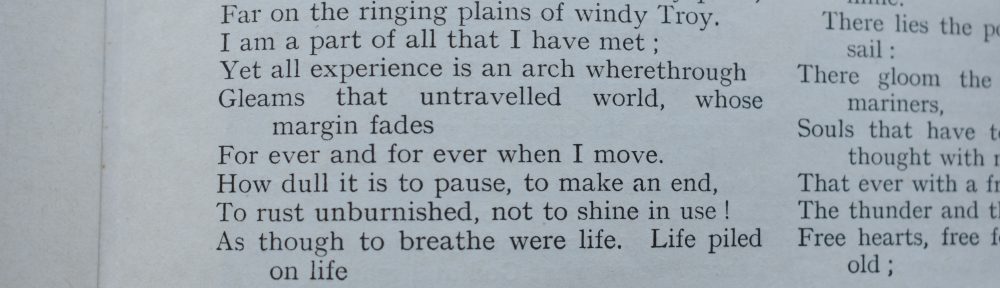

Technically, this novel reminded me of André Gide’s “Strait is the Gate”: words, phrases, opinions and settings that gain weight in retrospect. So:

- Stevens prefers artists’ sketches to photographs in the guides to English counties: an embellished view to the more accurate photograph.

- “Bantering is not a duty [a duty!] I feel I can ever discharge with enthusiasm”. However, he ends his account with a determination to work on his bantering skills to suit his American employer and serve him better. I see this either as being doomed to gruesome failure (his previous attempts at banter have failed Pooterishly), or as an optimistic sign that he is learning to loosen up and adapt to the 1950s. It’s certainly a very different and diminished notion of service from the one that enabled Stevens to usher Ribbentrop and Halifax into the house so discreetly.

- He – an ageing man – is travelling towards Cornwall – the end of the landmass. The novel ends on an evening. And the title! He also gets his clothes muddy on the journey.

- The idea occurred to me that this novel is Jeeves becoming the manservant of Roderick Spode, but it doesn’t work (it’s too bleak for that) . . . although there is one mention of newt-mating – surely a deliberate nod to Gussie Fink-Nottle?

- Stevens refers to his brother’s death and the loss to his father: “Naturally my father would have felt this loss keenly . . .”. Wow! Use of the conditional to express deduction. Do we infer from this that Stevens senior was even more buttoned-up than his son?

- Stevens’s words contradict his actions – aka he lies: he denies working for Lord Darlington a couple of times.

- The importance of silver-polishing in the novel’s symbolism. It’s the faulty silver-polishing that first hints at his father’s decline, and now Stevens is also losing his touch. And silver-polishing, as he has told us, used to be the measure of a good butler.

- Throughout it all is woven the yearning, prickly relationship-that-never-was with Miss Kenton. It is her letter – into which he reads too much – that sets Stevens off on his motoring journey, and their final parting is the one time when he admits to his heartbreak.

- I did find humour in it, but it went against the grain of Stevens’s narrative (again, like Mr Pooter), such as the expectation that he would give the facts-of-life talk to a young man.

Pingback: Below Stairs by Margaret Powell (1968) | Aides memoires part 3